Carbon fibre has been around since the late ’50s; however, it wasn’t until the ’60s that the full potential of carbon fibre became apparent. Lightweight, strong, durable and with the ability to be moulded into various shapes, carbon fibre is ideal for a multitude of manufacturing processes.

But what is carbon fibre? How is it made and what are its uses in car manufacturing?

In this article, we aim to answer all of your burning questions.

What is carbon fibre?

Carbon fibre is an extremely strong and lightweight material that has been used in a variety of industries, from the automotive industry to sports and even green technologies.

Carbon fibre is high in stiffness and tensile strength, has a low weight-to-strength ratio, has high chemical resistance, is temperature tolerant to excessive heat and has low thermal expansion properties. It is around five-times stronger than steel, and twice as stiff, yet is lighter in weight.

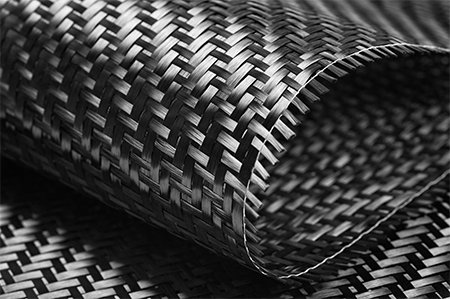

Incredibly, carbon fibre strands can be thinner than a single strand of human hair. These strands are twisted together to form a yarn-like product and then weaved together to form a strong lightweight material that can then be moulded into whatever shape required.

Who invented Carbon Fibre?

While there were early attempts at creating carbon fibres, notably by Thomas Edison in the 1870s for use in light bulbs, the invention of high-performance carbon fibre is credited to Roger Bacon.

In 1958, while working at the Union Carbide Parma Technical Center in the USA, Bacon’s research into the properties of graphite accidentally resulted in the creation of these strong, versatile fibres. This discovery paved the way for the development of carbon fibre composites used in a wide range of applications today.

What is Carbon Fibre Made Of?

Carbon fibre, despite its strength, is actually very lightweight. This impressive combination comes from the material it’s made from. Thin strands of carbon atoms, barely wider than a human hair, are tightly bonded together. These strands are produced from a starting point called a precursor, which is usually a type of organic polymer like polyacrylonitrile (PAN).

After going through a complex process that involves intense heat, most non-carbon atoms are burned away, leaving behind the strong, lightweight carbon fibre we know.

Is carbon fibre stronger than steel?

There’s a misconception that carbon fibre trumps steel in pure strength. Steel can actually withstand much higher compressive forces, making it a better choice for applications requiring rigidity, like building beams.

However, the true strength of carbon fibre lies in its strength-to-weight ratio. Imagine two beams, one steel and one carbon fibre, able to hold the same weight. The carbon fibre beam would be significantly lighter, a major advantage in cars, planes, and even bicycles.

This is why carbon fibre shines in weight-critical applications where superior strength is needed without sacrificing lightness.

How is carbon fibre made?

The precursor of around 90% of carbon fibre is polyacrylonitrile (PAN), a plastic made from acrylonitrile. To turn polyacrylonitrile or any other precursor into carbon fibre it must go through the chemical and mechanical processes outlined below:

1. Stabilising

Before the fibres can be carbonised they need to be chemically altered in a process known as stabilising. It is necessary to convert the fibres from linear atomic bonding to more thermally stable ladder bonding. In order to do this, the fibres are heated in air to between 200-300°C for anywhere between 30 to 120 minutes.

Under this heat, the fibres pick up oxygen molecules from the air which causes the atomic bonding pattern to rearrange into the more thermally stable ladder bonding.

2. Carbonising

Once the fibres have been stabilised, they are heated between 1,000-3,000°C for several minutes in a special pressurised furnace filled with a gas mixture that is devoid of oxygen. Under heat and pressurised conditions, the fibre’s bonds break down and start to lose non-carbon atoms in the form of various gases, including water vapour, ammonia, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, hydrogen, nitrogen and others.

As non-carbon atoms are expelled, the remaining carbon atoms form tightly bonded carbon crystals more or less parallel to the long axis of the fibre. These tightly-formed bonds give carbon fibre its characteristic strength.

3. Treating

After carbonising, the resulting fibre has a surface that doesn’t bond well with other materials. This means it would be difficult to use in manufacturing processes. As a result, the surface is oxidized slightly, this enhances the chemical bonding properties and also etches and roughens the surface slightly which improves its mechanical bonding properties.

4. Sizing

The final treatment in the carbon fibre making process is sizing. During this process, the fibres are coated to protect them from damage during winding and weaving.

Once they are protected, the very fine fibres are then wound onto cylinders called bobbins. The bobbins are loaded into a spinning machine and the fibres are twisted into yarns. The carbon fibre yarns can then be weaved together to form a usable carbon fibre product.

Advantages of Carbon Fibre:

Carbon fibre boasts a remarkable combination of properties that make it a valuable material across many industries.

Not only is it incredibly strong and stiff, but it’s also surprisingly lightweight, allowing for weight reduction in everything from aircraft to sports cars. Plus, unlike steel, it won’t rust or corrode, making it ideal for marine and wet environments.

Interestingly, carbon fibre is also X-ray transparent, allowing for inspections without dismantling equipment in some medical fields. It even expands and contracts minimally with temperature changes (low CTE) and resists many chemicals.

These unique properties, alongside its thermal and electrical conductivity, make carbon fibre a highly versatile and sought-after material for a wide range of applications.

What is Carbon Fibre Used For?

Carbon fibre, boasting an impressive strength-to-weight ratio, transcends the realm of racing bikes and futuristic spacecraft. Its unique properties have found applications in a surprisingly wide range of everyday products. From the high-tech world of prosthetics and medical implants, where its lightweight strength is crucial, to the more down-to-earth realm of fishing rods and sports equipment, where it enhances performance without sacrificing control, carbon fibre’s versatility is on display. Even musical instruments like violins and cellos can benefit from its exceptional stiffness and tonal qualities.

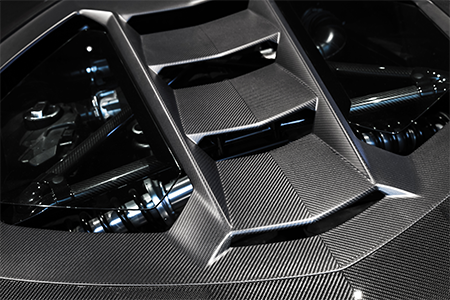

This unique combination has made it a star player in car manufacturing, particularly for high-performance and luxury vehicles where shedding weight is paramount. Beyond the iconic look it lends to supercars, carbon fibre’s presence can be found in various parts throughout the car. Engine bonnets, wings (or fenders), and spoilers are common applications, but it’s reach can extend to the entire roof, significantly lowering the car’s centre of gravity for improved handling and stability. This weight reduction translates into a multitude of benefits. Not only does it enhance a car’s agility and acceleration, but it also helps improve fuel efficiency – a win-win for both performance and environmentally-conscious drivers.

However, the use of carbon fibre in cars is not without limitations. Its high cost compared to traditional materials like steel makes it a more exclusive choice, often seen in high-end car segments. Additionally, repairs to carbon fibre components can be far more complex and expensive than conventional materials. Despite these drawbacks, carbon fibre’s impact on car design and performance is undeniable. As manufacturing techniques improve and potentially bring down costs, we can expect to see this wonder material play an even greater role in shaping the future of automobiles.

Is Carbon Fibre Expensive?

Compared to traditional materials like steel or aluminium, carbon fibre comes with a hefty price tag. This stems from several factors. Firstly, the raw materials used to create the fibres themselves are relatively expensive.

Secondly, the manufacturing process is intricate and energy-intensive, requiring precise control and specialist equipment. While research is ongoing to bring costs down, carbon fibre remains a premium material, often reserved for high-end applications where its unique properties of strength and lightness outweigh the initial expense.

Carbon Fibre Moulding

Traditionally, to turn carbon fibre into a useable, strong and permanent shape, the woven carbon fibre would be laid over a mould, coated with stiff resin or plastic and then heat-cured to form a solid shape.

However, a newer process, known as forged composite, is making carbon fibre production quicker and less expensive. Forged composite involves cutting the carbon fibre into short lengths of around 5cm, mixing it with resin and then injecting it into a mould to be pressed.

Uses of carbon fibre on cars

One of carbon fibre’s biggest selling points is that it can be used to make almost anything. However, the cost of producing carbon fibre has meant that until recent years, the use of carbon fibre in vehicle manufacturing has been confined to high-end, low-volume racing or concept cars.

Formula One has been instrumental in the development of carbon fibre. The McLaren MP4/1 was the first car on the Formula One grid to feature a carbon fibre monocoque chassis. At the time there was much speculation that the material would not withstand high-impact crashes common in this high-octane sport.

However, these fears were quickly eased during the practice for the 1981 Italian Grand Prix at Monza, when McLaren driver John Watson crashed at nearly 150mph. The engine and gearbox were torn from the MP4/1, yet the carbon fibre monocoque structure remained intact and John Watson walked away with no serious injuries. Since then, the use of carbon fibre in Formula One has become mainstream.

As ever, this has then fed down into other aspects of the motor industry. Carbon fibre quickly became, and still is the choice material for manufacturers to use when making concept cars. Its ability to mould to whatever shape required gives car designers more free rein to let their imagination run wild.

More recently, a fall in the production cost of carbon fibre has meant that carbon fibre made its way onto more mainstream models. In recent years, a number of car parts have been made from carbon fibre, including spoilers, side mirrors, roof panels, hoods, front grilles, front bumpers, air vents, chassis tubs, wheels, driveshafts, side skirts and rear diffusers.

Which car brands use Carbon fibre?

The use of carbon fibre extends across a range of car brands, but it’s particularly favoured by those known for their high-performance or luxury offerings.

Leading the charge are established names like McLaren and Ferrari, who incorporate carbon fibre extensively in their supercars, from the entire chassis for unmatched lightness to aerodynamic components for superior handling.

German giants like BMW and Audi are also embracing carbon fibre, with its presence increasing in performance trims and some electric vehicles, where weight reduction optimises battery range.

Even mainstream manufacturers like Ford and Toyota are starting to experiment with carbon fibre for specific components, suggesting this wonder material might become more widespread in future car designs.

Aston Martin

With the Aston Martin Vanquish Carbon Edition, Aston Martin took things to the next level. As well as carbon fibre body panels, it featured an exposed carbon fibre splitter, diffuser and sill blade.

BMW

BMW has been a key player in helping to bring carbon fibre to the mainstream. They have used it in their BMW-i models’ lightweight passenger cabins. A big part of the push for this has been to reduce weight to improve fuel efficiency to ensure the cars are better for the environment.

Ferrari

Ferrari has taken things a step further by developing carbon fibre wheels for the its 488 Pista supercar to reduce the weight of the wheels. This has helped to reduce both the inertia and rotating mass that the drivetrain has to deal with, which enables faster acceleration, sharper turning, cornering at higher speeds and more effective braking. The overall result – even better performance and greater driver enjoyment!

Carbon Fibre Wrap

If your car doesn’t currently benefit from carbon fibre, fear not. You can add carbon finishes to your car to increase its appeal and one of the most popular options is getting a carbon fibre wrap.

While this won’t help reduce the weight of your car so won’t bring any improvements in efficiency or handling, you do get a number of other benefits. First of all, it looks great and will ensure your car is set apart from other models on the market. Secondly, the carbon fibre wrap acts as a protective layer on your car and will help to protect your car against Mother Nature’s damage.

The future of carbon fibre

As the production cost of carbon fibre continues to fall and car manufacturers face even tighten emission standards, we think carbon fibre will become even more mainstream. Its lightweight, but strong properties mean it is the perfect material to help reduce the cars overall weight and therefore increase efficiency, while also improving the safety of a car’s occupants.